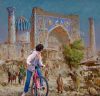

I was riding up my street, coming home from school. I always needed to stay pretty wide awake on the bike. There were no sidewalks in my neighborhood, my street was narrow, and drivers in Gulistan were often looking at their phones.

This day an old guy was wandering up the middle of the street. I rode up beside him and slowed down.

‘Salamat siz, Atalar. Hello, Grandfather,’ I said politely, stopping my bike.

‘Salamat sen, bala. Hello, son.’ He didn’t look surprised to meet a foreign kid.

But he did look lost, so I said in Gulsha, ‘My name is Joel. Can I help you, sir?’

‘No. I am going there,’ he said, pointing.

It looked like he meant past the end of my street, but why? There wasn’t a lot of anything out there.

Just fenced-off old ruined houses where a faded billboard said some developer one day was going to build a fancy estate.

‘Makul. Okay,’ I said. What was I going to do? Just ride home and leave him in the middle of the street?

A car was coming slowly from the direction of the Main Road, and the old guy was right in its path. I gently pulled him against one of the high garden walls that nudge the edge of the asphalt.

The car stopped and a lady and a man got out.

‘Oh, Apa,’ the guy said. ‘Kayda barasez? Dad, where are you going?’

The lady spoke to me in Gulsha. ‘I only left the apartment to pick up the children from school, and somehow he got out.’

‘Maqul,’ I said. ‘I thought he was lost.’

‘Oh, not really,’ the son said. ‘We used to live up there.’ He pointed like his father had. ‘You know, the old neighborhood. But the government moved us years ago, into an apartment block on Main Road.’

They were gently taking Atalar to the car, but he didn’t really want to go. I felt sorry for all of them, but I didn’t think about them any more after they left.

Not until about a week later and I saw the old guy walking up the street again.

Uh-oh.

He was walking a bit faster, and more like he knew where he was going this time.

I rode up beside him and said hello.

‘Hello, son,’ he said in Gulsha.

I got off the bike and walked beside him. How had he got here? Must have caught a bus and then tottered up here from the College Park shops.

His poor family. He had as much road sense as a toddler.

I looked back down the street, and, yep, there was the son’s old blue Mazda wobbling through the potholes towards us.

The lady and the gentleman got out, pretty stressed.

This time I felt really sorry for them all.

‘I locked the door!’ The lady said, like I might be judging her. ‘I don’t know how he opened it!’

‘Well, he’s safe now,’ I said.

‘Ha. Rakhmat. Yes. Thank you,’ the son said.

I asked, ‘Why does he suddenly want to come back?’

‘Oh.’ The man chewed his lip. ‘Our fault.’

The lady said, ‘He heard us talking. The houses are finally going to be bulldozed. There will be nothing there any more.’

‘When Apa heard that, he was upset,’ the son said. ‘He kept saying he had to go back and “find it”. Find the house I suppose.’

‘What if you drove him there and showed it to him?’

‘Joq.’ He shook his head. ‘We did that. He wanted to go into the house, and the area’s all fenced, and too dangerous.’

So they put him in the car, and we all said, ‘Khosh, goodbye,’ and they thanked me again, and they left.

Well, the lock on that apartment door really needed fixing, because only three days later, there was Grandfather walking up my street again.

All the exercise was doing him good. He was walking a bit faster and more in a straight line, but still in the middle of the road.

The son and daughter-in-law had been right about the bulldozers. I’d started hearing them this morning as I was getting ready for school.

‘Salamet siz, Atalar,’ I said, as I got off my bike beside him.

‘Salamet sen, bala. Qandai sen?’

‘Oh, I’m fine, thank you. Kayda barasez? Where are you going?’

He pointed in the direction of the old ruined neighborhood. ‘I have to find it!’

‘Makul. Okay. Find what?’

‘Shhh!’ He put his finger over his lips and looked around as if we might have a dozen people listening in. There was nothing in the street except two stray dogs, and several houses away, a bored security guard scratching his elbow.

Then around the corner came the blue Mazda, bouncing at speed over the potholes.

Grandpa, you are going to be in so much trouble this time.

Grandpa crushed a piece of paper into my hand. ‘Tapmak! Find it!’

I pushed the paper into my pocket. ‘If I find it, where do you live? What is your address?’

‘Block Seventeen, Entrance Four, Apartment Nine.’

The Mazda squealed to a stop. This time the lady was in tears, the guy was nearly chewing his lip off, and we finally introduced ourselves.

‘Menin atim Joel,’ I said as the son shook my hand.

‘Ramiz,’ he said.

His wife gave me a tired smile. ‘Menin atim Kinaaz.’

So then it was, ‘Come on, Dad,’ again, as they led him to the car.

I was left standing in the street with my bike, watching the blue Mazda make a tight back-and-forward turn and head back towards the Main Road.

The bulldozers had been working all day. Was there anything left up there, anyway?

I rode past my house, up to the old neighborhood.

Well, there weren’t bulldozers, to start with. There was one tracked yellow excavator loading rubble into a truck.

How would I find Grandpa’s house? The street signs had long gone, and so had a lot of the house numbers.

I smoothed the paper out. 639. Okay. I wheeled the bike along the road, finding numbers neatly painted on house front walls, slopped on gate posts, screwed onto front doors, stenciled on electricity poles. When there were numbers.

I pulled the bike through a gap in the fence and walked along a street inside. I was getting the pattern. It took me less than ten minutes, and I was standing in front of Grandpa’s house.

Green plants crawled over a lot of it, the open triangle between the iron roof and the top of the side wall had exposed the ceiling to the weather. Windows were broken and the front door had been bashed in.

‘Tapmak! Find it.’ What did he mean?

Not, Find the house. Ramiz had shown it to him. Today I’d seen things left behind in other houses – furniture mostly, but pictures on the walls, religious items, small stuff that maybe meant a lot to someone, once.

I pushed open the bashed-in door and walked around inside. Couldn’t see anything. Well, nothing that Grandpa might want. I opened the door of a small metal fireplace, had a good look, felt up the chimney, and only got a filthy charcoal hand.

I checked the kitchen cupboards and the cupboard in a bedroom. Nothing. I went back outside and looked up at that gap under the roof.

Down the street was a long panel of metal fence lying in a yard. I dragged it back to Grandpa’s and stood it up like a ladder. If it broke, I could think of several horrible ways I could get hurt.

The ceiling was strong wooden planks. I walked all over it, looking for anything he might have hidden when it was a closed space. Nothing. I went down the ladder as carefully as I’d gone up, and laid it back on the ground.

Was there a shed or any other place to hide something outside? Nope.

I rode home, cleaned myself up, did my homework and had dinner with the family. But I kept thinking about Grandpa.

The thing was … okay, he didn’t realize he was walking in the middle of the road and could get hit by a car. But he had the smarts to break out of his apartment, catch a bus, and find the route to his old house. He’d also thought ahead, remembered me, and written the house number down to give me.

He wasn’t totally doolally.

Which meant, I had to take him seriously.

So, next day in school I wondered every spare minute about where Grandpa might have hidden … what?

After school, I went back. The excavator had made a lot of progress in twenty-four hours. What had been houses yesterday were now heaps of bricks, concrete, broken timber, and twisted roofing iron.

The wrecking machine and I arrived at Grandpa’s house about the same time.

The heavy diesel engine revved and spewed black smoke and the tracks squealed and clanked.

The operator extended the long steel arm, opened the bucket jaws, ripped a small tree out by the roots and tossed it aside. He didn’t see me or the bike. He would have been shocked if he had.

He raised the bucket high, lowered it onto the iron roof and dragged it off with a screech like the end of the world.

I was inside now, protected by that strong wooden ceiling, desperately trying to think of one last place I could search. The floorboards? No. No sign of a trapdoor.

The bucket hit the bedroom wall with a crash, followed by the roar of falling bricks and a rumble as they bounced across the floor. Hit the wall again and another roar, the ceiling sagging over my head, the house filled with clouds of dust and grit.

But I’d heard something. Under the roar of the falling wall, the screech of the tracks, and the growl of the engine I’d heard one, other, distinct sound that wasn’t any of those.

As the excavator prepared for a third assault, I ran into the bedroom, threw bricks aside where I’d heard that high, metal clang! and scrabbled madly in the rubble. The rusty yellow bucket came in, dragging the mess out, and I was digging with my bare hands only a yard from it, and the operator didn’t even know I was there. He hooked the bucket through the window, dragged the last of the wall away, and I saw grey metal among the bricks on the floor, grabbed it and ran for my life out the front door.

I collapsed in the wild garden, shocked and shivering, my hands scraped raw and bleeding, the vibrations of the machine throbbing through the ground. But I’d found it. I’d found the brick-sized metal box Grandpa had hidden inside the bedroom wall.

I collected my bike and walked home, the box in my hand, my legs wobbly.

Mum saw me walk in. ‘Joel! You’re covered in dirt and grit. You look like you’ve been underground!’

‘Nearly. I’ve been up there where they’re pulling down those old houses.’

‘What?’

So I told her, and she listened, looking sympathetic about Grandpa and his family, then horrified at what I’d done. I showed her the box.

Living in Central Asia had made my Mum resilient. She said, ‘Well, brush yourself off a bit – comb the lumps of cement out of your hair at least – and we’ll go and search for this apartment.’

So she drove down Main Road, and we read the numbers stenciled on the run-down apartment blocks. We found ‘Seventeen’, and Mum parked in a dirt car park beside the kiddies’ playground. Women taking their washing off the drying lines stared at the two foreigners.

‘Seventeen’ was a long building with a big ‘4’ over the last door on the right. A man came out and left the door to close itself. We ducked in behind him, and climbed the concrete stairs. On the third landing we knocked on the door of apartment Nine.

Ramiz opened it. ‘Joel!’

I could hear a TV somewhere behind him, with a children’s program.

‘Salamet siz, Mr Ramiz,’ I said respectfully. ‘This is my mother, Laura.’

So he and Mum and then Kinaaz all said, ‘Hello, nice to meet you,’ in Gulsha, and I held out the metal box.

‘I found this in your old house. I think it’s what Atalar was looking for.’

They stared at it, eyes wide, mouths open.

Finally Ramiz waved his arm for us to come in, and pointed down the hall, and we went down there. Grandpa was sitting on an old brown couch in a small shabby living room. I went over and presented the box with two hands, carefully laying it in his lap.

He looked at it for a long time, slowly picked it up with shaking hands, then tears trickled down his cheeks. It was like the box had brought itself to him. Grandpa had tried so hard to get to it, and it had called out, Here I am!

Maybe I was hardly in this story at all.

Grandpa closed his fingers over the combination lock, and without hesitation rotated the correct numbers, the lock fell off and he raised the lid.

Even standing back I could see it was folded papers, and a few old photos. He took them out, one by one, unfolding the papers, looking at them and handing them to his son.

Ramiz took them, started reading, and had to go and sit in an armchair.

‘What are they?’ Kinaaz asked him.

‘Investment certificates, bank accounts, I don’t know what all of them are.’

‘This is money? That belongs to us?’

‘To Dad. I think. To us, our family.’

I looked at Mum, and she gave a tiny nod towards the door.

Gulanis always offer cups of tea and biscuits to visitors, but this wasn’t the right time.

Better for us to quietly leave while they were distracted.

If they wanted, they could find our house.

There was no hurry. Not any more.